Scotland’s Arctic Connections

Scotland’s strong ties to the Arctic stretch back through the centuries – and we’re committed to ensuring they endure for centuries to come.

Scotland is one of the Arctic region's closest neighbours and we share far more similarities than you might think. Whilst many of these are most visible in our northern regions, social, cultural and economic links stretch right across the country and are at the heart of our strong friendship with the High North.

The connections between Scotland and the Arctic can be traced back many centuries. Until the end of the 15th century, Scotland’s Orkney and Shetland islands were actually part of the Norwegian-Danish Kingdom. The Shetland Islands were actually gifted to Scotland in 1469 as part of the dowry when Princess Margaret of Denmark married King James III of Scotland. Even today, many of the town names in the northern parts of Scotland can trace their origins back to Nordic roots.

From David Livingstone’s expeditions through Africa to John Muir’s travels across America, Scotland has produced some truly remarkable explorers. It should come as no surprise then, that quite a few Scots have also made pioneering inroads into the Arctic region throughout history. One example of this is John Rae – perhaps one of Orkney’s most famous sons.

John Rae

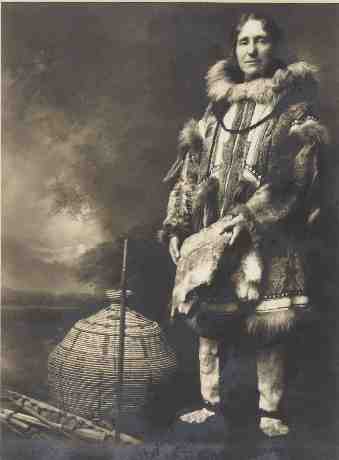

.jpg) Though a surgeon by trade, Rae was also an incredibly successful explorer and is credited with discovering the final portion of the Northwest Passage – now named the ‘Rae Strait’ in his honour. Skilled at hunting, navigation and travelling long distances with little equipment – living off the land – Rae became so successful in the region due to his treatment and understanding of local indigenous cultures.

Though a surgeon by trade, Rae was also an incredibly successful explorer and is credited with discovering the final portion of the Northwest Passage – now named the ‘Rae Strait’ in his honour. Skilled at hunting, navigation and travelling long distances with little equipment – living off the land – Rae became so successful in the region due to his treatment and understanding of local indigenous cultures.

At a time when interacting with natives was shunned by his European counterparts, Rae instead chose to embrace them. He considered himself a student of the local Cree and Inuit people and learned from them, many of the skills that made him so successful. He would go on to become one of the foremost experts on native methods of Arctic exploration and survival, using these methods to map the uncharted northern regions of Canada.

Isobel Wylie Hutchison

Isobel Wylie Hutchison is another Scottish traveller and explorer famed for her expeditions to the Arctic region. Primarily a botanist, Hutchison also wrote poetry and books during her travels and was a frequent contributor to magazines including National Geographic. Throughout the 1920s and 30s, Hutchison embarked on several journeys throughout the region, including trips to Iceland, Greenland, Alaska and the Aleutian Islands.

Isobel Wylie Hutchison is another Scottish traveller and explorer famed for her expeditions to the Arctic region. Primarily a botanist, Hutchison also wrote poetry and books during her travels and was a frequent contributor to magazines including National Geographic. Throughout the 1920s and 30s, Hutchison embarked on several journeys throughout the region, including trips to Iceland, Greenland, Alaska and the Aleutian Islands.

Much like her predecessor, Rae, Hutchison set herself apart from her contemporaries by her attention to detail of the daily lives of the local indigenous groups. When not writing about her travels, Hutchison spent time painting or filming the locals wherever she travelled and today her works can be found everywhere from art galleries to national libraries - her life has even inspired modern Scottish entrepreneurs like Imogen Russon-Taylor, who used Isobel as the inspiration for one of her fragrances.

Moving Forward Together

As climate change issues continue to present an ever-increasing threat to our planet’s health and wellbeing, it is more vital than ever that we maintain our close links to this region. Just as any good friend would do – we’re committed to helping out our frosty neighbour to the north, not just for its own good, but for the good of the entire world.

However, we also understand that these issues are too great for us to solve alone and that success depends on countries coming together to collaborate and tackle these problems together.

That’s why, on 23rd September, Scotland is launching its Arctic Framework. This framework not only sets out the wealth of Scottish expertise that can be utilised to tackle many of the Arctic’s current issues, it also reflects on the common challenges shared by our two regions – everything from connectivity to cultural heritage.

We’ve laid out a few of these key areas below, and highlighted some of the amazing projects happening.

Climate Change & pioneering research

Simply put, climate change is the defining challenge of our time and so it’s unsurprising that tackling it is one of Scotland’s main priorities. We recently called for collective action from countries around the world by declaring a global climate emergency and have already put in place our own climate change bill – generally regarded as the toughest of its kind in the entire world – and aim to reach 100% reduction of greenhouse emissions by 2045.

From Hywind – the world’s largest floating offshore wind farm – to the MeyGen array – the world’s largest tidal stream project, Scotland is home to innovative, world-leading renewable energy projects that are helping lead the charge. Not only that, we are phasing out petrol-powered cars by 2032 and investing heavily in reducing emissions from all our transport methods.

Scotland also has a long tradition of pioneering Arctic research and, since 2000, our universities have contributed more than 1000 academic publications dedicated to the Arctic region. We are home to Europe’s largest glaciology research group and two of our universities (University of Aberdeen & University of the Highlands and Islands) are founding member of the University of the Arctic - a network of academic institutions from across the world that carry out research in and about the region.

Rural locations & indigenous languages

Scotland is just packed full of stunning vistas, rolling hills and glens and jaw dropping landscapes, but that also means that a large portion of the country is rural – 98% to be exact. Throughout the Highlands and Islands, the population density is just nine people per square kilometre – very similar to large parts of the Arctic region.

These beautiful, pristine landscapes present a range of common challenges that Scotland and the Arctic countries can work together to address. These challenges include issues around de-population and the provision of health services, as well as connectivity, transport and general higher costs in rural areas. Digital connectivity in particular is essential for empowering rural areas and, since 2014, broadband access in Scotland has risen from 61% to 92%.

The Scots & Scottish Gaelic languages are important parts of Scotland’s rich history and cultural heritage. Because of this, we understand all too well the desire for our Arctic neighbours to preserve and promote their own indigenous dialects.

The future of protecting these ancient languages can be found in the technological world and we are seizing the opportunities afforded by modern digital tools. E-Sgoil, for example, is allowing teachers based in the Western Isles to deliver real-time, interactive lessons in Gaelic to students right across Scotland.