Scotland’s historic role in the ongoing fight against racial discrimination

As a nation, Scotland has and continues to stand up against racism.

On this, the UN’s International Day of Elimination of Racial Discrimination, we look to Scotland’s past to point to a better and brighter future; one where we are all judged on our skills and contribution, not the colour of our skin.

Much of Scotland has a murky past, our hands stained by our ancestors’ role in the slave trade and Empire. However, Scots - and the democratic and egalitarian ideas of the Scottish Enlightenment - also played a pivotal role in the eventual abolition of slavery.

From education, to fund-raising and support, and even football, Scotland has a long and proud history when it comes to combatting racism and racial discrimination.

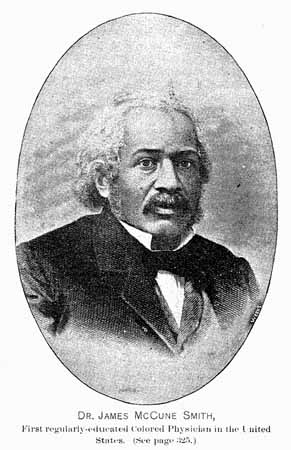

James McCune Smith

Take the case of Glasgow University graduate James McCune Smith (1813-1865), who was born into slavery, yet went on to become the first African American to hold a medical degree - which he gained in Glasgow.

Take the case of Glasgow University graduate James McCune Smith (1813-1865), who was born into slavery, yet went on to become the first African American to hold a medical degree - which he gained in Glasgow.

Set free on July 4, 1827, at age 14, by the Emancipation Act of New York, Smith attended the African Free School, in Manhattan, where he was described as an "exceptionally bright student".

Upon graduation, he applied to Columbia University and Geneva Medical College in New York State, but was denied admission due to his race.

Encouraged by a former teacher, he went on to apply - and be accepted - to study medicine at the University of Glasgow. Smith kept a journal of his sea voyage, and after arriving in Liverpool and walking along the waterfront, he thought, "I am free!"

Smith was no slouch when it came to his studies. He graduated at the top of his university class in 1835, staying on in Glasgow to gain a master’s degree in 1836, and a medical degree in 1837.

Armed with these qualifications, he returned to New York where, for the next 28 years, he worked for the good of his fellow citizens, practising as a doctor and running his own public pharmacy.

In 1863 Smith was appointed professor of anthropology at Wilberforce College, Ohio. He died two years later on November 17, 1865, at the age of 52 – only 19 days before ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, which finally abolished slavery across the United States.

Smith never forgot his time in Scotland, and Glasgow hasn’t forgotten him. Later this year, Glasgow University, his alma mater, will open a new, £90m learning hub named in his honour.

Frederick Douglass

.jpg) A contemporary of Smith, and another African-American abolitionist who found support and attentive audiences in Scotland was Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) - who even took his ‘freed’ name from a character in Scottish author Sir Walter Scott’s romance, The Lady of the Lake.

A contemporary of Smith, and another African-American abolitionist who found support and attentive audiences in Scotland was Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) - who even took his ‘freed’ name from a character in Scottish author Sir Walter Scott’s romance, The Lady of the Lake.

Born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, Douglass escaped from slavery in Maryland, to become a national leader of the abolitionist movement.

Douglass, a firm believer in the equality of all peoples, whether black, female, Native American, or recent immigrant, found common cause in Scotland.

Douglass visited us 1846 as part of near-two-year tour of Britain and Ireland. He stopped first in Glasgow, which despite the city benefiting financially from the country’s involvement in slavery and the slave trade, had been home to a vibrant anti-slavery community for many years.

Douglass drew huge crowds to his talks and speeches in Glasgow, before heading north to Perth, then south to Ayr, the birthplace of one of his literary heroes, Robert Burns. There, Douglass met with Burns’s sister, Isabella Begg.

In all, Douglass spent nearly five months in Scotland, attracting huge crowds in Arbroath, Paisley, Kilmarnock, Fife and Dundee. He thought Edinburgh the most beautiful city he had ever visited.

In a letter home to an abolitionist colleague, he wrote: “I enjoy everything here which may be enjoyed by those of a paler hue – no distinction here.”

Even when it comes to football, our national game, Scotland has always been colour blind to talent.

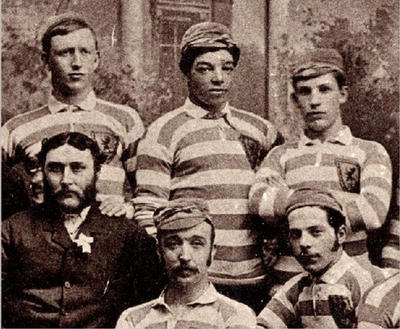

Andrew Watson

Andrew Watson (1856-1921), born of a Scottish father and a Guyanese mother, is widely regarded to have been the first black international football player.

Andrew Watson (1856-1921), born of a Scottish father and a Guyanese mother, is widely regarded to have been the first black international football player.

After attending school in England, Watson, then aged 19, came ‘home’ to study at the University of Glasgow, where he found more interest in football than he did in his books.

He dropped out of university after just one year to go into business but played for local amateur sides. After first playing for Maxwell in 1876, Watson signed for local side Parkgrove, where he was additionally their match secretary, making him the first black administrator in football.

On 14 April 1880, he was selected to represent Glasgow against Sheffield; Glasgow won 1–0 at Bramall Lane.

In April 1880, he signed for Glasgow’s Queen’s Park FC – then Britain’s largest football team – and became their secretary in November 1881. He led the team to several Scottish Cup wins, thus becoming the first black player to win a major competition.

Watson won three international caps for Scotland. His first came in a match against England in London on 12 March 1881, in which he also captained the side. Scotland won 6–1, which (as of 2019) is still a record home defeat for England. A few days later, Scotland played Wales and won 5-1.

Watson's last cap came against England in Glasgow on 11 March 1882. This was a 5-1 victory again to Scotland.

Glasgow teams, and fans, it seems held a particular fondness for black and Asian footballers.

Mohammed Salim

In 1936, Celtic FC welcomed Calcutta-born player Mohammed Salim into their team.

In 1936, Celtic FC welcomed Calcutta-born player Mohammed Salim into their team.

A five-time winner of the Indian League title, with Calcutta's Mohammedan Sporting Club, Salim, playing without football boots, stunned Celtic boss Willie Maley with his ball skills.

He played in just a few matches - earning the nickname 'The Indian Juggler' - before he felt homesick for India.

Celtic pleaded with him to remain in Scotland for a season, even offering to organise a charity match on his behalf and promising him five percent of the gate money.

Salim played, but refused the cash, asking that the money be donated to the city’s orphans.

He returned to India in time for the 1937-38 season and played out the rest of his days with the Mohammedans side in Calcutta.

Salim died, aged 76, in 1980.

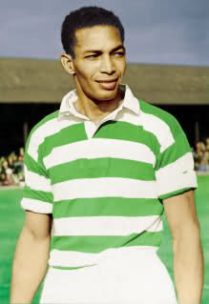

Gilbert Heron

Another famous face to find favour at Celtic Park was Gilbert Heron, the first black player to sign for the club.

Another famous face to find favour at Celtic Park was Gilbert Heron, the first black player to sign for the club.

Born in Jamaica in 1922, Heron, the father of musician Gil Scott Heron, moved to Canada as a youth and later enlisted in the Royal Canadian Airforce. As well as being a track athlete and a boxer, he played football and broke through during his stay there.

He was spotted by a scout from Glasgow Celtic while the club was on tour in North America and he was signed by them in 1951, becoming their first black player, and one of the first to play professionally in Scotland.

Heron went on to score in his debut match, but only played five first-team games in all. Despite that, he was a favourite with the fans, earning the nickname ‘The Black Arrow’ for his speed and accuracy with the ball.

After being released by Celtic, Heron went on to play with another Glasgow team, Third Lanark. While living in city, he played cricket with leading local clubs such as Poloc CC. He later became a published poet, with one of his works, 'The Great Ones', describing leading players from his time playing football in Scotland.

The future

Today, in the worlds of sport, industry, academia, and entertainment, Scotland still welcomes and values the contributions of all races, and rallies around the claim of ‘One Scotland, many cultures’.

Because no matter what your race, creed, colour or culture, you’re welcome here. After all, it’s the contribution of the many, that makes Scotland what it is: one great country.

The truth is, all of us – living, working, laughing, sharing and loving life in Scotland – have more in common than that which divides us.

This is Scotland standing up for what matters at a time when it couldn’t matter more. Because the reality is – and the evidence shows – a more equal, more diverse society makes for a more productive, happier society. So, it’s with pride we say that in Scotland there’s no ‘them’, there’s just you, me and we.

And we are Scotland.